On February 28, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris will mark the reopening of its newly renovated fashion galleries with an exhibition devoted to Harper’s Bazaar. “First in Fashion” will examine the history of fashion as it has unfolded in the pages of the magazine, spotlighting a collection of watershed moments and seismic shifts in the way we dress, think, and live as they were captures in—and, in some cases, instigated by—Bazaar. Overseen by MAD director Olivier Gabet and curators Éric Pujalet–Plaá and Marianne Le Galliard, with Bazaar’s editor in chief, Glenda Bailey, and design director, Elizabeth Hummer, the exhibition charts Bazaar’s evolution from a 19th-century literary lifestyle journal that billed itself as “a repository for fashion, pleasure, and instruction” into the first modern fashion magazine.

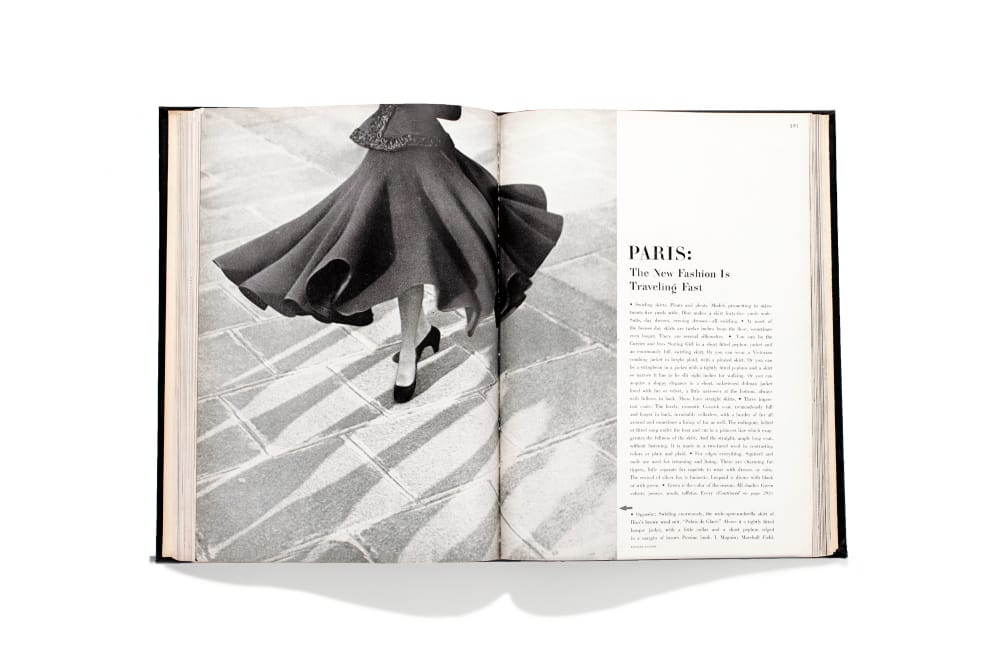

A story on the “New Look”, photographed by Avedon for the October 1947 issue

The name of the exhibition is fitting. Since its founding in 1867, Bazaar has been present for an epoch of “first” in fashion, as well as myriad creative, cultural, and social revolutions.

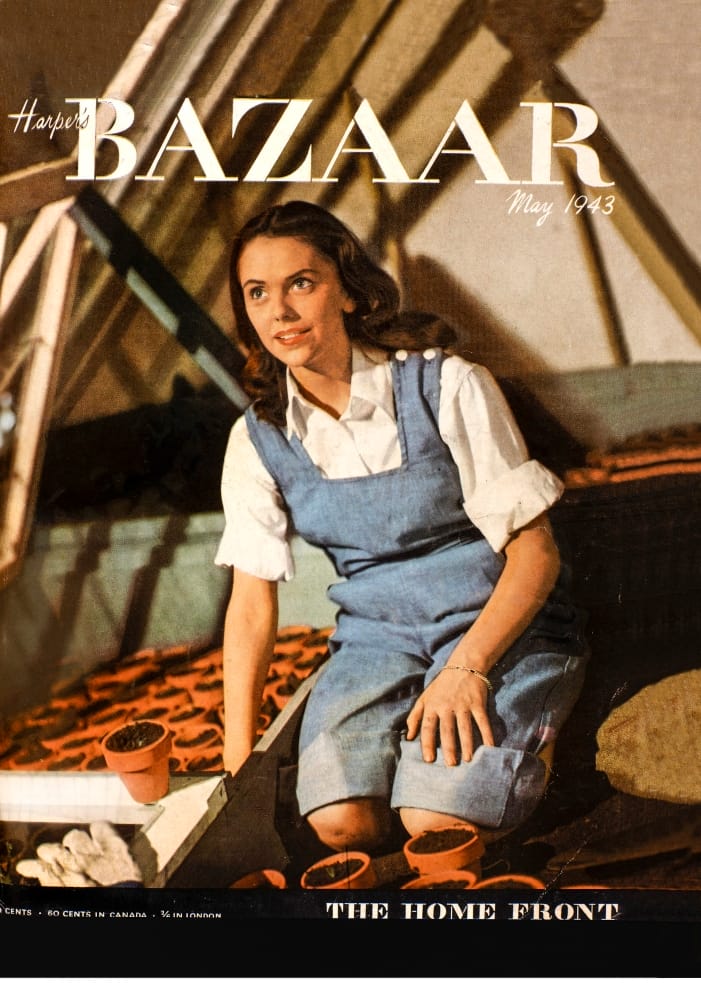

Bazaar—or Bazar, as it was originally spelled—was the first American magazine to dedicate itself to exploring the lives of women through fashion. Bazaar’s first editor, Mary Louise Booth, was involved in the women’s suffrage movement, and it was one of the first mainstream publications to advocate for voting rights, equal pay, and educational and professional opportunities for women. Bazaar was the first magazine to look at fashion within the context of art and culture, and the first to depict women in fashion in real environments, moving through real spaces in real time. It was the first magazine to commission Richard Avedon, and the first to anoint denim and bikinis as fashion (the latter of which Diana Vreeland deemed “the most important thing since the atom bomb”). Bazaar was also the first to celebrate Dior’s New Look, the first to put a man on its cover, and the first to introduce Kate Moss to America.

The list of creative talent who launched their careers in Bazaar and contributed to the magazine is equally impressive. Editors like Bailey, Booth, Carmel Snow, Nancy White, Anthony T.Mazzola, and Liz Tilberis all shepherded Bazaar during long, transformative periods. Creative and art directors like Alexey Brodovitch, Hanry Wolf, Marvin Israel, Ruth Ansel, Bea Feitler, Fabien Baron, and Stephen Gan broke new grounds and helped change the visual vocabulary of magazines. Artists like Erté, Christian “Bébé” Bérard, Marcel Vertès, A.M. Cassandre, Man Ray, Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dalí, and Andy Warhol all did illustrations for Bazaar. Writers and editors like Vreeland, Daisy Fellowes, Gloria Guinness, Eugenia Sheppard, Carrie Donovan, Tonne Goodman, Paul Cavaco, Sarah Mower, Melanie Ward, and Carine Roitfeld brought in new perspectives on fashion. Photographers like Avedon, Martin Munkácsi, Toni Frissell, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Lillian Bassman, Melvin Sokolsky, Hiro, Francesco Scavullo, Patrick Demarchelier, Peter Lindbergh, Jean-Paul Goude, and Karl Lagerfeld, who shot for Bazaar, expanded the potential of fashion imagery.

Steve McQueen photographed by Richard Avedon for the February 1965 issue

The MAD show is firmly grounded in fashion, drawing upon the museum’s robust archive of more than 150,000 pieces. But the thread of Bazaar’s ongoing dialogues with fashion animates much of the material.

The way Bazaar has covered fashion was undeniably shaped by the moment at which it as born. Patterned after a German publication called Der Bazar, Bazaar was originally conceived as a general interest weekly aimed at the women of the rising American leisure class that would cover fashion and the aristocratic social swirl in places like London, Paris, and Vienna, and offer advice on topics such as homemaking and etiquette alongside fiction and poetry. Under Mary Louise Booth’s leadership, Bazaar delivered glitzy coverage of the codes, clothes, manners, and modes of old-world high society, with a smattering of New York for good measure. But it also encouraged women to think more consciously about the roles that were being imposed upon them—domestic and otherwise—and even rethink aspects of their own lives and possibilities.

Bazaar was at once of its time and ahead of its time. An essay in the June 12, 1869, issue argued for “fairer laws for women, the opening to them of new avenues of employment, the gradual approximation to the just rule of equal wages for equal work, and the very general admission that is a few years all judicial distinctions between the rights of the two halves of humanity will be swept from the statute-books.” This was more than 50 years before the 19th amendment was ratified in 1920, guaranteeing women the right to vote.

It wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century, as designers like Paul Poiret and later Coco Chanel, Madeleine Vionnet, Jeanne Lanvin, and Elsa Schiaparelli cast off the old strictures of the Victorian era, that Bazaar began to more closely resemble the magazine it is today. But Bazaar’s definition of fashion had already come to embody the spirit of what Carmel Snow would later refer to as “well-dressed women with well-dressed minds.” The question of what it means to live as a woman in the modern world has hovered over the magazine for 153 years—and is one that’s at the centre of the MAD exhibition.

The cover of the May 1943 issue featuring a denim playsuit by Claire McCardell, photographed by George Hoyningen-Huene

“Visualize yourself as you looked on a beautiful autumn day last year,” Bazaar implored in the August 1947 issue. “There’s not much in the old picture that survives.”

In some ways, that is fashion: a powerful gust that blows through each season leaving a Rorschach of adjusted hemlines, reimagined silhouettes, and artistic, cultural, social, political, and economic implications in its wake. To Bazaar, though, the job of fashion magazines has never been just to describe the weather. It’s to be the wind.