The iconic film reflects a bygone era that glamorized hustle culture and laid the groundwork for the girlboss archetype.

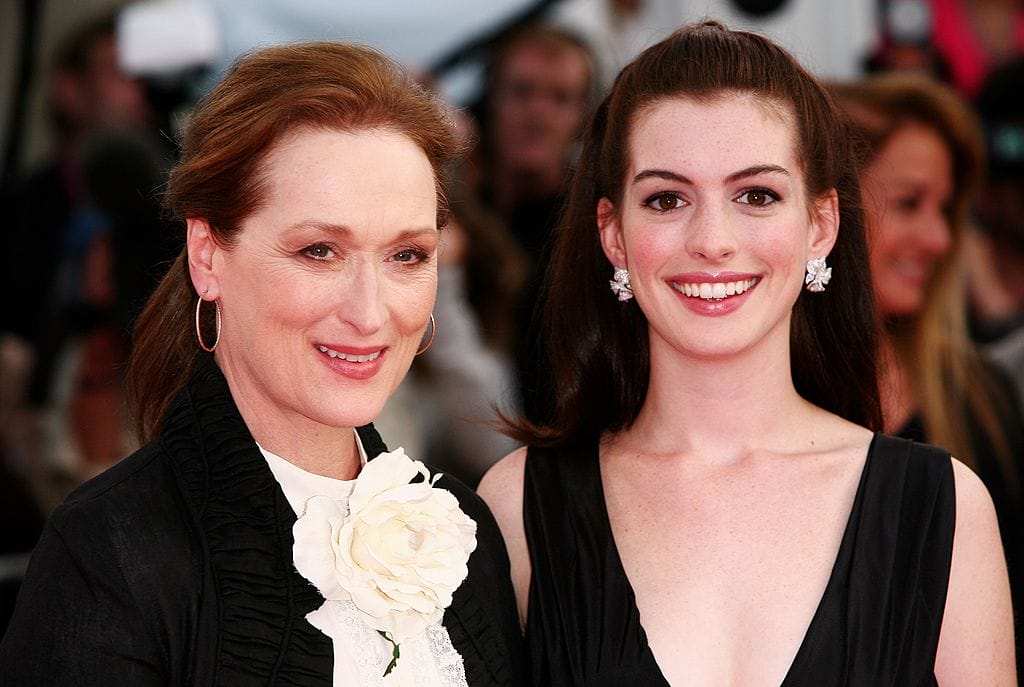

Runway Editor-in-Chief Miranda Priestly (Meryl Streep) is stuck in Miami due to a hurricane, which she insists is nothing more than “just drizzling” rain. She orders her new assistant, Andy Sachs (Anne Hathaway), to find her a flight back to New York City so she can catch her daughters’ school recital the next morning.Despite making countless frantic calls in the middle of Times Square and even contemplating calling in the National Guard for a last-minute assist, Andy fails to complete the task. It’s the first time she doesn’t rise to the occasion on the job, and Miranda predictably lambasts her for not being able to control the weather.

Photo by Arnaldo Magnani/Getty Images

The Devil Wears Prada, which marked its 15th anniversary this week, is just as much a film about working in magazines as it is about perpetuating the propaganda that having a boundaryless work ethic is the only way to propel your career forward. It glamorized hustle culture long before the term was common vernacular. After all, when “a million girls would kill for that job,” as Andy is so frequently told, what’s the harm in having no work-life balance and being subjected to constant verbal and psychological abuse from your boss? The movie wants us to believe that opportunity is payoff for enduring such abuse. Andy deals with the low salary, lack of benefits, and snooty colleagues all for the mere possibility of professional development down the road. “Being Miranda’s assistant opens a lot of doors,” Andy tells her concerned father over dinner. “I swear, this is my break.”

The movie wants us to believe that opportunity is payoff for enduring such abuse.

Getting your “big break” is a popular trope in several romantic comedies of the early aughts. How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days (2003), 13 Going On 30 (2004), and Hitch (2005) all tell stories of ambitious young journalists who find themselves in truly bizarre situations—a 10-day bet to make a strange man fall in and out of love; a time warp 17 years into the future; an operation to unmask an elusive date doctor—while simultaneously having to prove their worth in the workplace as their breakthrough moments loom. Andie Anderson (Kate Hudson) is close to being able to write about whatever she wants for her how-to column, Jenna Rink (Jennifer Garner) is tasked with reinventing the magazine she’s always dreamed of working for, and Sara Melas (Eva Mendes) is on the verge of becoming New York City’s top gossip columnist.

Photo by Francois Durand/Getty Images

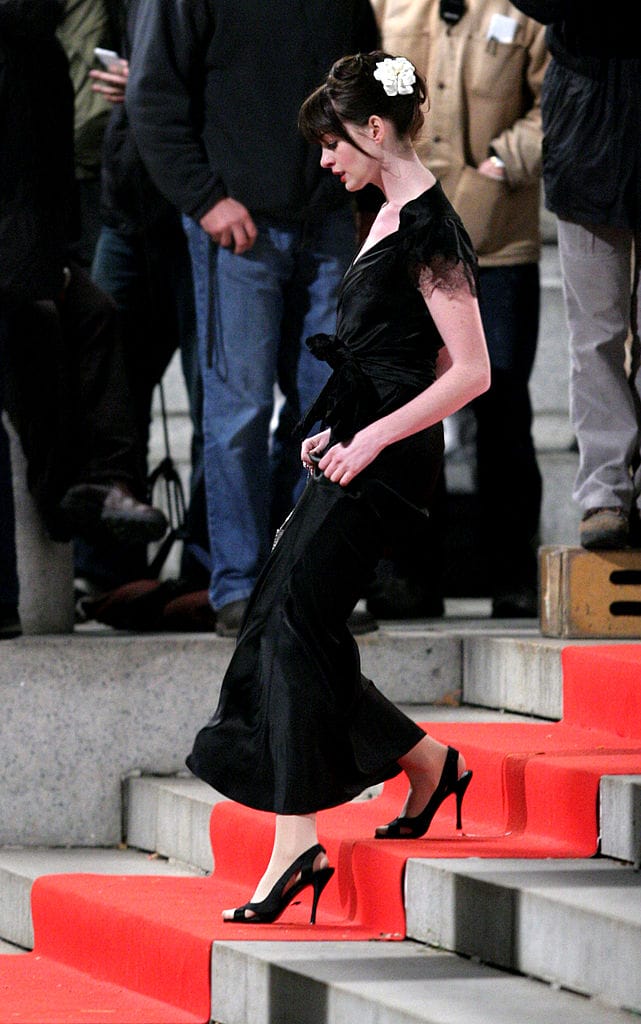

Like Andy, these women refuse to jeopardize their big break in any way because—as far as they know—it’s the only shot they will ever have. And so, they sprint around the city in designer dresses, taking urgent calls on their flip phones in between Starbucks runs, answering to demanding superiors and catty colleagues, and making themselves miserable and stressed beyond belief.

These films laid the groundwork for the girlboss archetype that would go on to dominate the discourse surrounding women and the workplace over the last decade. They tried to sell a modern version of the driven, headstrong career woman who will do just about anything to establish her professional credibility. It was an attempt at crafting a 21st-century Mary Tyler Moore. If you say yes to everything and everyone—and you “lean in” with relentless enthusiasm and devotion for your job—you, too, can be rewarded with a corner office, a fancy title, and the admiration of your peers. Never mind that it will cost you your sanity.Fifteen years after The Devil Wears Prada, the girlboss backlash is in full swing. The term itself is now considered passé. It’s been rendered obsolete perhaps by overuse and by sheer cynicism at what a girlboss is supposed to even be. More often than not, the images of so-called girlbosses thrust into the spotlight were that of white women. Its linear vision of corporate success—that is to be white, conventionally attractive, and generally privileged to begin with—doesn’t hold up in growing critiques against capitalism today, or the toxic work environments that girlbosses went on to create.

Photo by James Devaney/WireImage

From Away to SoulCycle to Theranos, there are countless examples to choose from.

That’s what makes the myth of the big break so insidious. It manipulates women into accepting that success is delivered in a singular fashion.

One could argue that Miranda was a quintessential girlboss—a rare, high-profile female leader calling the shots at a glitzy, capitalistic enterprise. (No doubt her backstory would be entertaining fodder for a prequel.) She was also—and let’s be honest here—a totally toxic superior who, in the end, was more interested in upholding the status quo than in reinventing it, despite having all the power and authority to do so. She wanted Andy to believe that saying no to her would be the end of her career, even though she knew Andy had all the potential in the world to make it without her or her connections.That’s what makes the myth of the big break so insidious. It manipulates women into accepting that success is delivered in a singular fashion. If you screw up once, that’s it. You had your one opportunity, and now you will never have another ever again.The reality is that big breaks aren’t a finite resource. They may be infrequent, but they can happen more often than you think—especially once you free yourself from the false belief that they can’t. And while that may not look exactly like tossing your phone into a fountain à la Andy in Paris, however you choose to shatter the big break myth is better than continuing to buy into a tired fantasy.

This article originally appeared on Harper’s Bazaar U.S

Photo by James Devaney/WireImage

Photo by James Devaney/WireImage