Patek Philippe hosts its fifth Watch Art Grand Exhibition in Singapore

It’s true what they say, “You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation.” It never occurred to me that I would eventually embrace the message of the Swiss watchmaker’s ‘Generations’ campaign until my mother gifted her Patek Philippe watch just weeks before I was set to attend the fifth installation of Patek Philippe’s Watch Art Grand Exhibition in Singapore.

I felt like I was part of the brand’s rich 180-year-old history as I arrived at Marina Bay Sands Theatre at the exhibition which boasted ten themed rooms with more than 400 exceptional timepieces plus a space dedicated exclusively for Singapore, in which the country celebrated 200 years as a city-state this year. “The history and relationship between Patek Philippe and Singapore is long storied from one generation to the next, and we wanted to bring the Genevan manufacture here to Singapore. What we have created here is a unique exhibition,” said Thierry Stern, president and chief executive of Patek Philippe, as well as fourth generation scion of the illustrious watchmaking family.

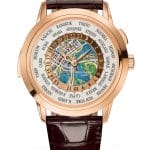

Among the standout timepieces and some of my personal favourites that were on display included pocket watches from the early 16th-century; Patek Philippe’s world’s first perpetual calendar wristwatch made in 1925; and not to mention the Calibre 89 which was designed for the brand’s 150th anniversary, and for over 25 years, it was the world’s most complex watch with 1,728 components and 33 complications. On top of that, Patek Phillipe unveiled six limited-edition watches ranging from sports watches to grand complication pieces, and all aesthetics inspired by Singapore and the Southeast Asian region.

The brand’s commitment in continuing Genevan artistic savoir-faire was exemplified in the Rare Handcrafts Room, where watch artisans demonstrated elaborate enamelling, engraving, wood marquetry, and hand-guilloché techniques. “The main goal of having this Grand Exhibition is really to educate people and to give a passion to newcomers and collectors,” said Stern.

I had a moment with Dr Peter Friess, curator of the Patek Philippe Museum Geneva. The former watchmaker gave BAZAAR an insight into his role of managing, maintaining, and continuing the legacy of the world’s most important watch collection.

Dr Peter Friess, curator of Patek Philippe Museum Geneva

How do you relate your background in art history with your work?

I started my career as a watchmaker. I have a masters degree in watchmaking and a full education as a restorer in watches, so I am very savvy when it comes to clocks and watches, and I had built my own timepieces. On top of that, having a PhD in Art History helps me create a cultural background behind all this. I think this combination really helps the museum get an added value.

What do you find most interesting about watchmaking, and how does Patek Philippe fit into this equation?

Watchmaking is the red thread through European history from 1300 onwards up until today, because the craftsmen who work with their hands and the scientists who work with their brains, are constantly exchanging information and finding inspiration for new innovations. So for me, watchmaking is an essential part of European history.

Patek is a big player. What I like in Patek—and you can see it in this exhibition—is that when you walk through it, you’ll learn that this company uses the brain of people and the mechanical skills of their fingers to build the most beautiful timepieces of the world. You will not find many companies like this and one that does it at this level.

Patek Philippe created a replica of the Patek Philippe salon in Rue du Rhône in Geneva

What would you say became the turning point for the manufacture, in all its illustrious history?

Philippe and Patek discovered the stem-winding and time-setting system. This is basically the first of its kind back in 1842. Patek added the crown to the watch before we had the key. You know that when you lose the key, you wouldn’t be able to wind the watch anymore! Therefore, the crown was attached to it so you would never lose it. With that innovation, the company turned the market upside down within 10 years. They had to find the watchmakers who build that movement and trained them, and it was all in accordance to what Philippe wanted. It was a game changer. Today, every mechanical watch we have has a crown, so I’d say the biggest contribution from this company to the history of timekeeping is adding the stem-winding and setting mechanism.

What is it like to be a caretaker of some of the most important timepieces in history?

Patek Philippe puts a lot of trust in its curators and people working at the museum because it’s not only me; it’s a large group of people. And when you are talking about an archive such as Patek Philippe’s, it is bound to be an amazing experience. There are very few people who have access to these archives, and I am lucky enough to be one of the few able to access them at any given time.

Are there many more mysteries to be solved or discoveries to be made for the brand?

We always think we know everything but we always have surprises. Sometimes we even have surprises on ourselves, too.

Patek Philippe displayed more than 400 exceptional pieces at the exhibition