Survey exhibitions allow us to track ways in which a single artist reflects on ideas and reconfigures their craft over time. While this reveals much about the individual, it crucially offers insights into the wider culture through which they move. Thus, we can use ‘At the end of the day, even art is not important’ as a lens to view the flowering of contemporary art in Malaysia and Southeast Asia. The dramatic social, political and technological changes that gave rise to this Golden Period in the 1990’s-2000’s echoed throughout Southeast Asia, resulting in a host of contemporary practices regionally. The snapshot of a multi-valent practice that emerges through ‘At the End of the Day, even Art is not Important’ is in fact representative of what has been happening throughout the region.

Curated by Shabbir Hussain Mustafa, Senior Curator of National Gallery Singapore, ‘At the End of the Day, even Art is not Important’ solidifies Ahmad Fuad Osman’s position as one of the definitive Malaysian artists. Primeval Landscape II (1991), which was created during the artist’s final year in UiTM, indicates his innate talent, giving way to a room of abstract and neo-expressionist works. For Fuad this early period formed a training ground for the formal aspects of creating art including composition, scale, colour, perspective—essential tools for succinct visual communication. This insistence in perfecting basic technique subsequently allowed him to move seamlessly across several genres and styles of mixed mediums.

Power Is So Sweet That Whoever Tastes It Wants More, 2008, Ahmad Fuad Osman encapsulates a daily scene

Walking through the mid-career survey exhibition, audiences will not only note a variety of mediums, from painting to sculpture, installation and new media, but a range of conversations. Fragile: Handle with Care (1996) is a personal rumination on mortality, while Quarantine (2009) tells us of Fuad’s own experience with Islamophobia. Other works including Dreaming of Being a Somebody, Afraid of Being a Nobody are political in nature. Enrique di Malacca Memorial Project, now in its third iteration after stagings at Singapore Biennale 2016 and Sharjah Biennale 2019, brings history into contemporary consciousness, while questioning the veracity of truths laid down by colonial powers.

Halfway through ‘At the End of the Day, even Art is not Important’, Ahmad Fuad Osman’s survey exhibition at National Art Gallery Kuala Lumpur, audiences are confronted by Kerauhan (2014/2019). At first glance, the wall spanning oil on canvas seems familiar, leaning heavily on classical Western painting traditions—namely finely painted figures along a religious theme. A second look reveals its resolutely contemporary nature. The perfectly rendered figures are passionately engrossed in a Balinese Hindu ritual, set against a glorious (if stormy) skyscape. And here we have the genius of Fuad, as he elevates Eastern theology and knowledge while engaging audiences in a conversation on the various appreciations they have for the developed and developing worlds. A recently made confident statement on skill and intellectualism, Kerauhan informs audiences that this senior Malaysian contemporary artist’s star continues to ascend.

This installation encapsulates a hospital feel with clinical smells. Mat Jenin is (Always and Always Will Be) Dreaming To Death, 2019, Ahmad Fuad Osman

Setting the exhibition against the historical backdrop of the 1990’s is telling. Contemporary Malaysian art began taking root in the 1980’s, precipitated by luminaries such as Fauzan Omar, and the 1990’s are when the movement really exploded. This time also saw the emergence of the MATAHATI collective, of which Fuad is a founding member, which really exemplified contemporary Malaysia—in terms of its art scene as well as its society.

Comprising of Ahmad Shukri Mohammed, Ahmad Fuad Osman, Bayu Utomo Radjikin, Hamir Soib and Masnoor Ramli, the MATAHATI represented the urbanisation of the Malay population, while embodying the truly contemporary shift in society. Prior to the MATAHATI, multi-disciplinary practices existed locally, but the five young artists pushed the boundaries of what it meant to make art in the now. Never before had so many disparate mediums, genres and topics been aggregated, and the trends they set still resonate. Look towards Shukri’s use of non-art materials in his mixed media works, or Hamir’s theatrically monumentous paintings such as Pilihan (2005), which extended what was accepted as ‘art’.

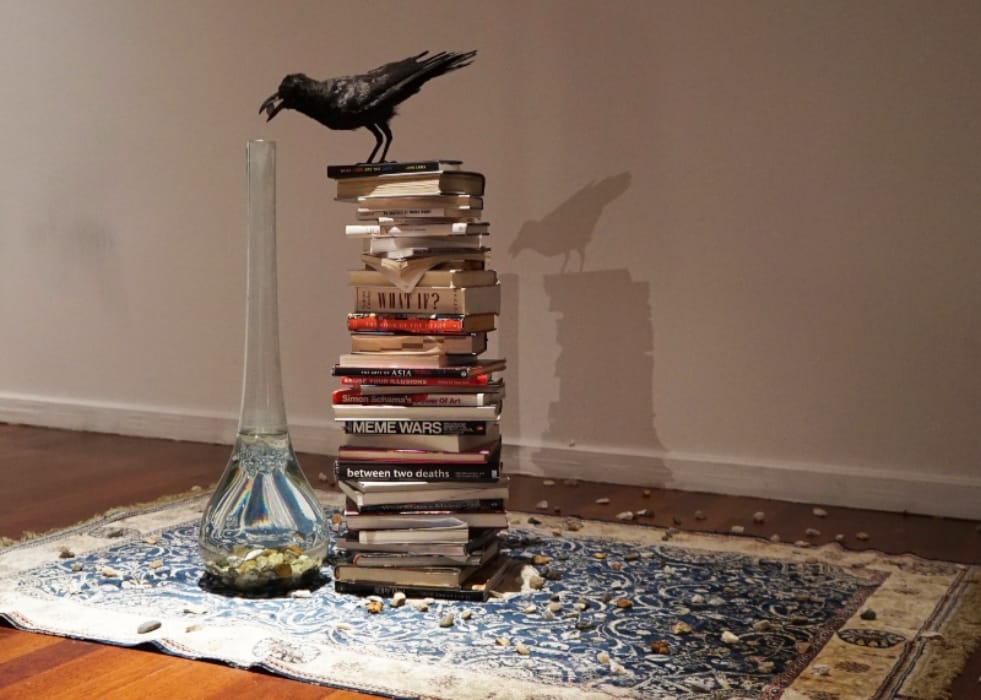

A taxidermy crow, present in This Is Certainly Not What We Thought It Was, 2014, Ahmad Fuad Osman

The use of the figure as site for discourse that recurs in Fuad’s practice is not foreign amongst his peers. Leading artist of Indonesia’s post-Suharto era, I Nyoman Masriadi utilises slick superhuman figures in witty, occasionally sharp-tongued, commentary on contemporary life and pop culture. While Masriadi’s conversations have global resonance, he speaks in a distinctly local voice. It seems that this trait is one audiences respond to; in 2008 Masriadi was the first Southeast Asian artist to have an artwork exceed seven figures at auction when his triptych Man from Bantul (The Final Round) (2000) sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong for USD$1.1 million. In Thailand, Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s video works pair the human form with other motifs in the creation of meditative, complex imagery, challenging society’s moral sense and tolerance. Niranam (Nameless), with which she represented Thailand at Documenta 2012, exemplifies this, while alluding to the sculptural influence of her earlier practice through a strong sense of physicality.

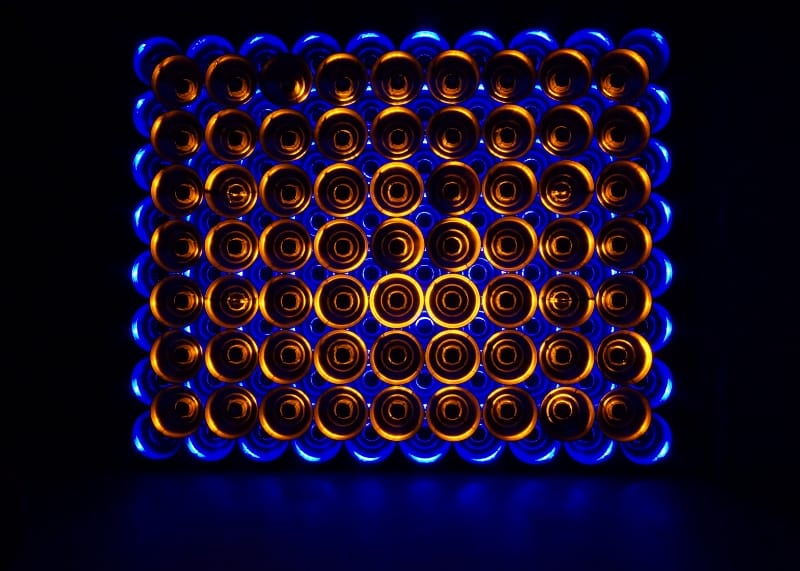

SONICreflection, 2016, transmits sounds and voices through speakers made of woks

Indeed, sound and moving image are popular amongst Southeast Asian artists, in works that often bring other genres into play—look at Fuad’s mix of painting and sculpture with sound and video in Enrique di Malacca Memorial Project. Singaporean artist Zulkifle Mahmod handles complex conversations with a similarly interdisciplinary approach, integrating audio and three-dimensional form to create ‘sonic territory’. SONICreflection (2016) transmits an amalgamation of sounds and voices from Singapore’s multi-cultural communities through speakers fashioned from woks, as endowing the ephemerality of sound with a sculptural abstraction.

A bedrock of Southeast Asian identity, multiculturalism is often addressed in the contemporary arts. Ronald Ventura’s paintings and sculpture mix different Eastern and Western cultural signifiers to discuss the multiple facets of Philipino identity which can be extended and understood across the region. Layering images and ideas over another, he reinforces the notion that for Southeast Asian artists skill and concept have equal importance, as they turn to well-made artworks to transmit the complicated discourse that describes the rapidly transforming landscape of Southeast Asia today.