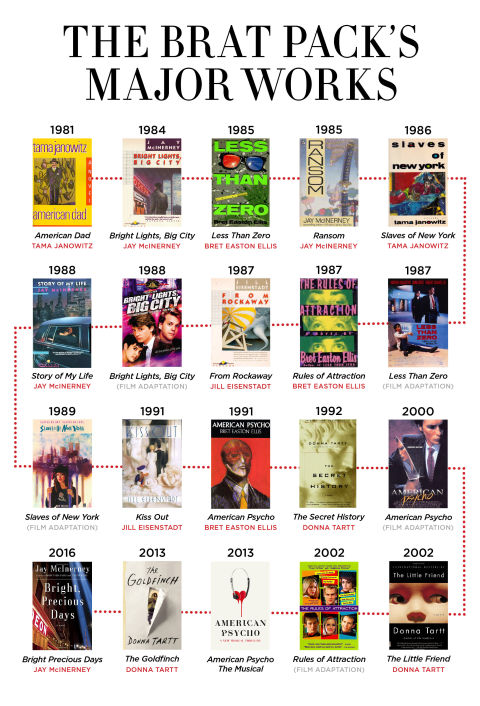

The hedonists. The provocateur. The phenom. The forgotten talent. In the decadent 1980s, the media shipped novelists Jay McInerney, Bret Easton Ellis, Tama Janowitz, Donna Tartt and Jill Eisenstadt into a loose-knit group known as the “literary brat pack.” One member would go on to win a Pulitzer; one would become better known for controversy than fiction; another would exemplify the excessive highs and very public lows of the decade; and another would slowly fade from view.

A generation of readers loved them. Critics largely despised them. And for a time, they were celebrated for their youth as much as their work. But they also helped change the course of American literature—and looked great doing it. “I think we made fiction fun again,” says McInerney.

The Odeon | Image: Getty

Jay McInerney was 26 in 1981. He was an Odeon regular, alongside his friend Gary Fisketjon, a Random House editor he’d met when they were both in undergrad together at Williams College. McInerney had worked as a fact-checker at The New Yorker, before he started selling his short stories, but that job wasn’t for him—or at least the magazine didn’t think so. He went to the Odeon to pick up women, but it also featured prominently in his newest story, “It’s Six A.M., Do You Know Where You Are?” which he’d just sold to The Paris Review. So it was also sort of like research.

A year later, that first short story would finally run and McInerney’s career would start to fall into place. And a few years after that, the Christian Science Monitor’s Hilary DeVries would call his debut Bright Lights, Big City“1984’s trendiest novel.” She’d place him and a few other “under-30 novelists” in the “literary brat pack”: young writers who were rumored to spend more time in downtown bars and nightclubs partying until dawn instead of writing. Just like Hollywood at the time, which was in the middle of a youth movement—their “brat pack” corollary included Judd Nelson, Emilio Estevez, and Molly Ringwald—the literary world was, too. The term wasn’t meant to stick to the writers, but it did, and for decades after, they would be tied to the label.

It was a great party for a few years. But like everything else in the 1980s, it had to crash sooner or later.

In the fall of 1982, Bennington College creative writing teacher Joe McGinniss—famed for being the youngest living writer to have a #1 New York Times nonfiction bestseller, at 26, for 1969’s The Selling of the President 1968—called his friend Morgan Entrekin, then an editor at Simon & Schuster, with a proposal. “I have the most interesting student writer I’ve ever seen,” McGinniss said, and added: “He’s a freshman.”

Entrekin was wary. People pitched him book ideas all the time; most were busts. And anyway, how could a college freshman have written something that good? But he bit, and what McGinniss gave Entrekin—a handful of journal entries from a young Los Angeles student named Bret Easton Ellis—would end up being better than nearly anything he’d seen in his career thus far. Entrekin recognized the same kind of generational chronicling in Ellis’ work that made writers like Kurt Vonnegut and Thomas Pynchon the trippy literary voices of the ’60s counterculture. The editor was barely a decade older than Ellis, but he could tell this was something different. And he knew it could sell.

At Bennington, Ellis found a mentor in McGinniss, along with a group of other students looking to make it as writers. By sophomore year, thanks to McGinniss and Entrekin’s interest, Ellis was far ahead of his classmates. Finishing his “project” became an obsession. Around Thanksgiving of 1982, Ellis traveled down to Manhattan to meet with Entrekin to talk about his writing. Ellis’ father had an apartment at the Carlyle, so he stayed there, Entrekin recalls. “He had mono or something—he was deathly ill. He just seemed really withdrawn.” But the work spoke for itself: “The pages, to me, were amazing,” says Entrekin. He found them fascinating enough that he sent excerpts to editor friends at Harper’s and Rolling Stone to see if they’d be interested in publishing it. He never heard back.

Bret Easton Ellis, Gary Fisketjon, and Jay McInerney in June 1987 | Photography: Patrick McMullan

Less Than Zero came out in May of 1985, a month after the NYU panel, and was the year’s big sensation, just as Bright Lights, Big City had been a year earlier. “This is one of the most disturbing novels I’ve read in a long time,” Michiko Kakutani wrote in a laudatory review of the debut.

By 1986, Ellis and Eisenstadt had moved down to New York. Ellis was now the bright young star; Eisenstadt had submitted her semi-autobiographical novel about kids in a Queens beach town; and Tartt, naturally, was the class valedictorian. McGinniss seemed almost hell-bent on helping his favorite students get book deals. When Eisenstadt received word that Simon & Schuster wanted to pay the recent grad $5,000 for her novel, McGinniss made some calls, and soon Knopf doubled their offer for her book. Not long after that, Sydney Pollack bought the rights to the film for another $50,000.

Stories about McInerney’s flirting and late nights were more popular than discussions of his work.

McInerney and Ellis were soaking up success. After the publication of Less Than Zero, the press made it seem like they were attached at the hip, reporting on their late nights out and comparing their books any chance they could, as they both centered around young, good-looking people doing drugs and living miserable lives, all lit by the neon glow of the early 1980s.

Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis, 1990 | Photography: Catherine McGann

The “toxic twins,” the press called them, since they, sometimes along with Fisketjon or Entrekin, were often spotted at trendy New York clubs like Area, or Tribeca dives like Puffy’s and Racoon Lodge, drinks in hand, eyes bloodshot. “I think there was a sense that we were having too much fun,” McInerney believes. “The literary establishment’s pretty conservative. Writers are supposed to be these sort of introverted loners who are badly dressed. We didn’t fit that mold.”

Read more on Harper’s BAZAAR U.S ‘Who Are the Literary Brat Pack?’